By Luna Sarti

In their Plastic Water: The Social and Material Life of Bottled Water (MIT Press, 2015), Gay Hawkins, Emily Potter, and Kane Race investigate “how and why branded bottles of water have insinuated themselves into daily life and the implications of this for safe urban water supplies” (xxii). In asking what is at work in the decision to move from drinking from the tap to drinking from the bottle, they advocate for an understanding of market arrangements in relation to consumers who recognize the distinct qualifications surrounding the product while incorporating the product into their world (xxxiii).

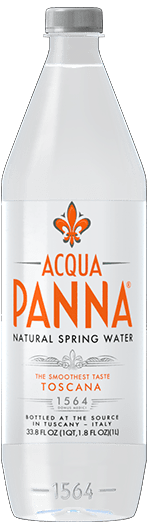

Although a diversity of elements and devices have been identified in the making of water into a “fast-moving consumer good” (FMCG), there is some agreement between scholars in identifying narratives of nature, purity, and human health as the key elements in the processes whereby bottled water has been transformed into a FMCG in the last few decades. However, there seems to be an emerging trend in the bottled water business to feature history as a crucial element in branding their products. Such a shift toward historicity should not be underestimated. Hawkins, Potter, and Race suggest, in fact, that the bottle of water should be approached “as an unfinished or entangled object” whose nature demands careful elaboration (xvi). Using Evian as a case study for bottled spring waters, they discuss how waters become singularized and distinguished by analyzing dynamics captured by processes of rebranding and “the ways in which they generate multidimensional relations that feed back into market processes and shape them in predictable and unpredictable ways” (34). If for a long time it was important to detach the imaginary of bottled waters from human activity and position them on the side of nature by stressing ideal characteristics such as spring waters untouched quality and their uncontaminated features, one should start wondering why historical dates are increasingly appearing on spring water brands such as Poland Spring, Acqua Panna, and San Pellegrino (all managed by Nestlé Waters).

Since the key issue with water is that it can be turned into a market object in many different ways, it is crucial to pay close attention to the specific historical processes whereby it is “rendered economic” in the sense described by Fabian Muniesa, Yuval Millo and Michel Callon in their introduction to Market Devices (3). Such a shift towards a historical aura for bottled waters could have interesting implications, particularly for social and historical analyses.

This question first came to my mind when noticing that following the cross-platform campaign that Nestlé Waters North America launched last May, Acqua Panna’s bottle label emphasizes the year 1564, the Italian word for Tuscany (“Toscana”) as well as a stylized fleur de lis, the emblematic symbol of Florence, and – only on the glass bottle- an explicit reference to the Medici family. The year represents such an important detail that it is also impressed in the plastic bottle, whereas the glass bottle has the brand name “San Pellegrino” impressed which replaced “natural spring water” that characterized the old bottle. While for decades water companies tried to construct an imaginary that severed their water products from human interaction, Nestlé Waters seems to be now trying to establish a sense of historicity for Acqua Panna by connecting today’s bottled waters to Florence and the time of the Medici.

That history represents an important aspect of Acqua Panna’s identity, particularly since its acquisition by Nestlé Waters in the late 1990s, is confirmed when looking at its official website. While traditional informative sections of bottled waters focus on themes such as water quality, mineral content, PH levels, and the water shelf-life, Acqua Panna has included since the early 2000s a section on its history, which is now addressed as the fourth question in their FAQ section for the US website.

FAQS section – 4. What is the history behind Acqua Panna?

“Acqua Panna takes its name from the Villa Panna Estate in Tuscany, a summer estate that was owned by the noble Medici family of Florence. The Medici family were of the most renowned art patrons in history. Their court included some of the most celebrated artists & visionaries including Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Galileo, and Botticelli. The iconic fleur-des-lis symbol was their crest. The Medici family acquired over 3,000 acres of land in Scarperia, Tuscany in order to turn it into an untouched hunting reserve. They officially limited its borders with an act, dating back to 1564. That decree still exists and guards the land where Acqua Panna flows.” From The US website of Acqua Panna. © 2015 Nestlé

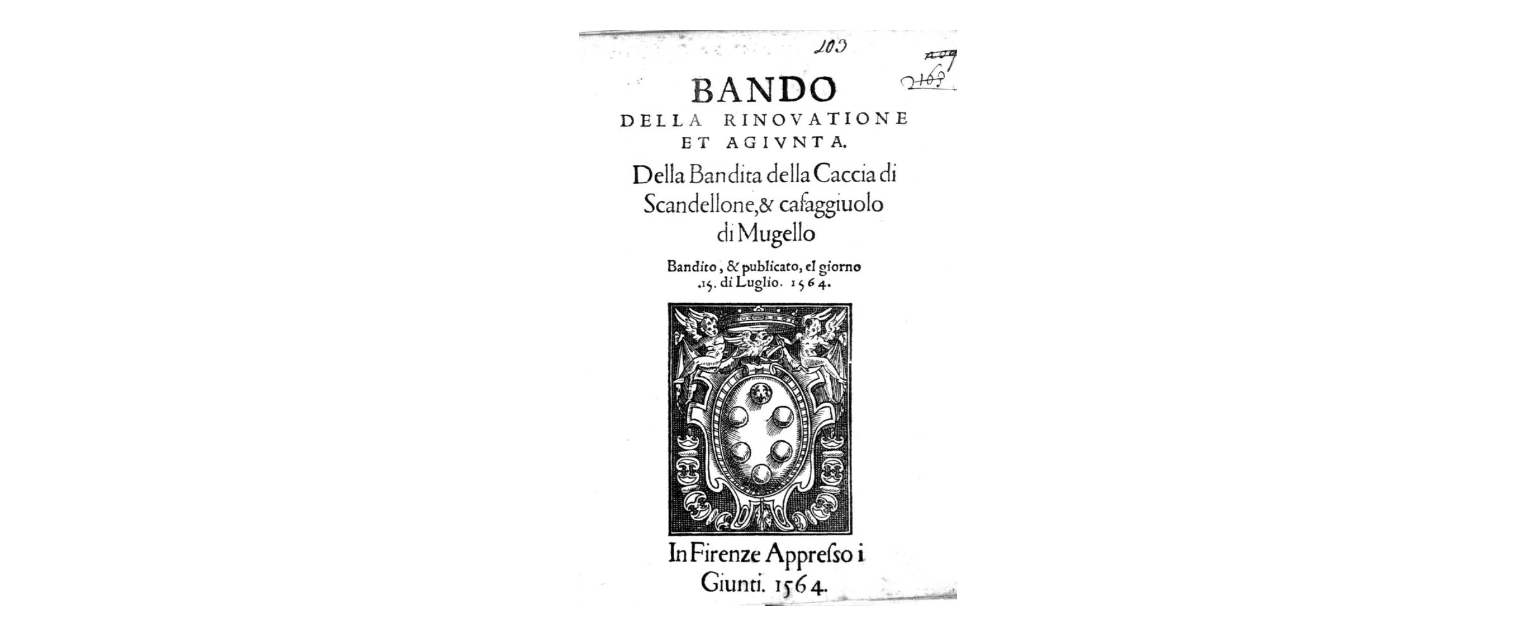

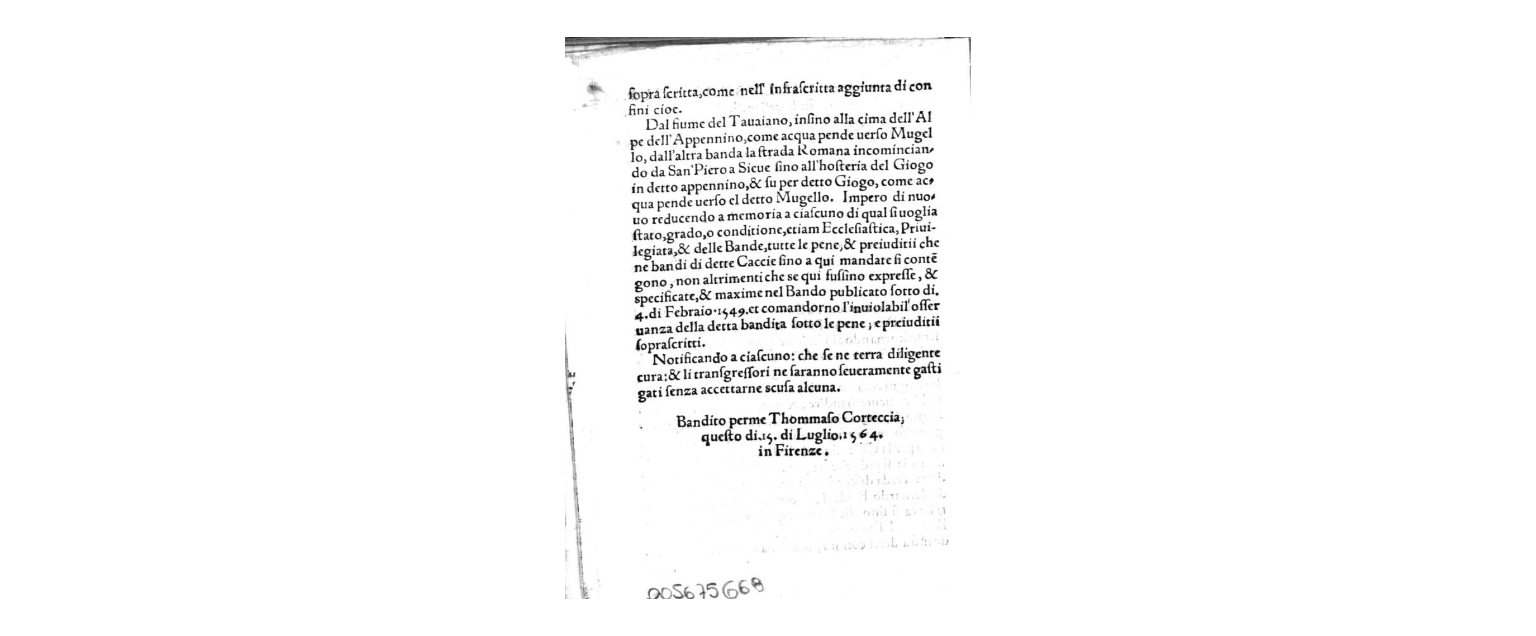

Certainly, in 1564 the bandita (featured in the gallery below) of Scarperia , which included the villa of Panna and local springs, was transformed into the Duke’s game reserve, thus effectively preventing the local community from accessing the spring water within its borders. However, the Bando focuses on establishing the borders of the reserve, and the Medici never bottled their water nor commercialized it. It was the Marquise Luigi of Torrigiani who acquired the reserve in the 19th century and started bottling and selling Acqua Panna (as Acqua sorgiva di Panna) in Florence.

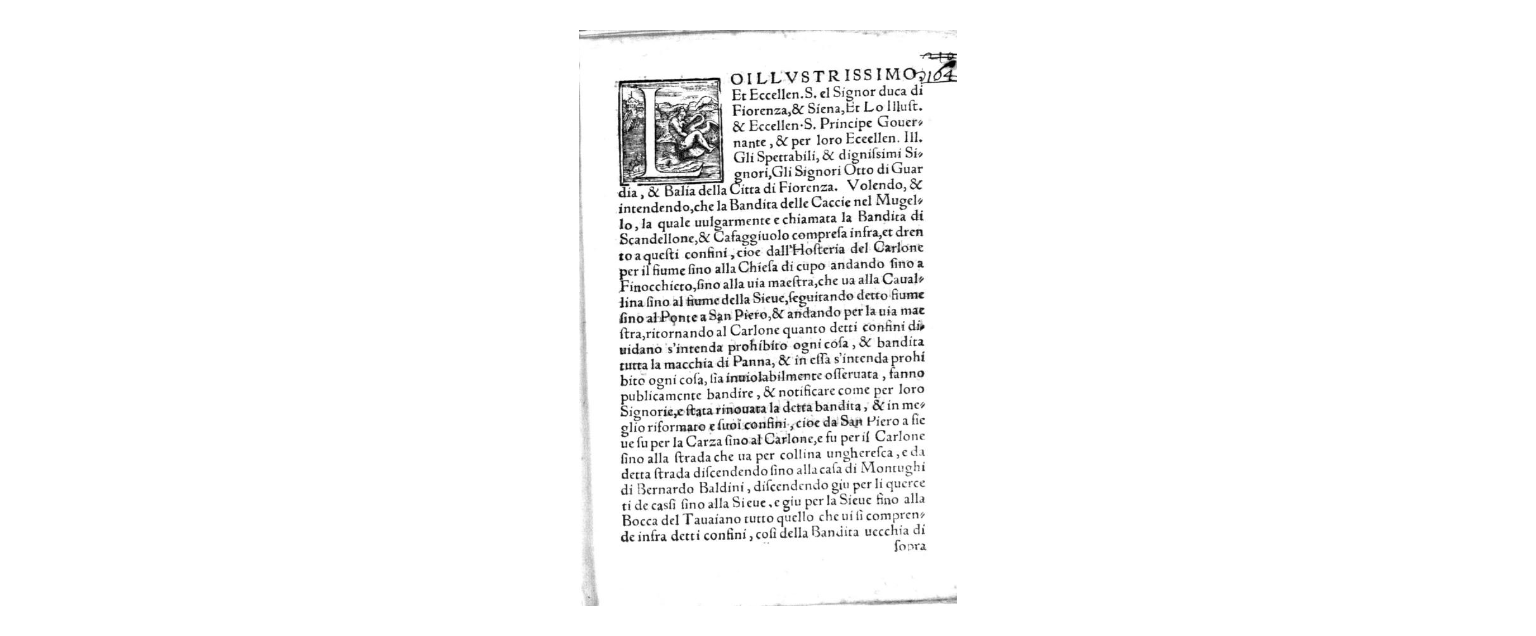

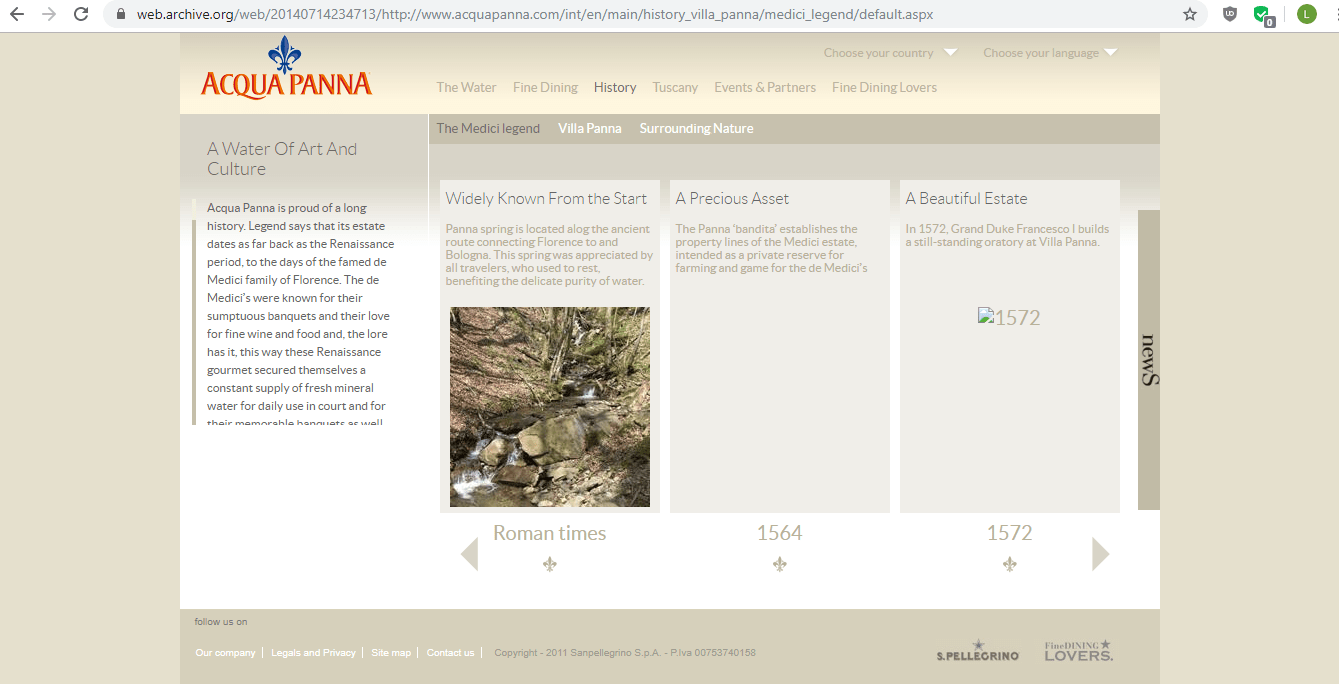

Using WebArchive it is possible to look at the way in which the historical discourse was reshaped over time. A snapshot of the website taken between August 8, 2013, and July 14, 2014 (featured in the gallery below), shows how Acqua Panna originally featured a proper story line on their website, spanning from Roman times to the year 2006. The story line pinpoints several events for each century. For the 16th century we find the aforementioned establishment of the reserve in 1564 and the construction by the Grand Duke Francesco I of the oratory at Villa Panna in 1572. Moving forward, the timeline includes the image of an extant cabreo documenting the estate in 1792, along with the location of the villa of Panna, and then shifts to the year 1860 when the Marquise of Torrigiani for the first time sold the waters from the estate in Florence in 54-liter demijohns. For the 20th century, there are references to the year 1910, which is highlighted as the year when the Marquise Luigi Torrigiani started to use liter bottles for Acqua Panna, the year 1938, when the Count Contini Bonaccossi who bought the estate from the Torrigiani family founded the “Società Panna”, and then the acquisition of the company by the San Pellegrino Group in 1956, which was later bought by Nestle in 1997. All of these references to events that somehow signal a shift in the commercialization of this water have disappeared in the 2019 rebranding.

As I continue to investigate the complex processes that make the international assemblage that is today Acqua Panna, I ask myself why history is becoming more important to constitute contemporary bottled waters and why a particular history has been selected in the process to singularize Acqua Panna from other waters. Inspired by Plastic Water to rethink packaging as “something that helps bring new realities and practices into being that have socially binding effects” (6), I wonder if this historicization of the label and of bottled waters might be an attempt to play against the growing awareness of what plastic waters mean for our material world. Perhaps, as public discourse around the impact of plastics in marine ecosystems grows and campaigns against bottled waters intensify, it becomes difficult to sustain the association between nature and bottled waters that for so long played a role in the marketing of plastic water. It would make sense then to reshape the narrative around Acqua Panna and place it at the center of the Medici myth. Away from nature, via history, this bottle shapes a time-honored lifestyle.

Luna is a Ph.D. candidate in Italian Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research explores the shifting cultures and practices of water that bound the Arno river in Florence. In her dissertation, she analyzes site-specific medieval and early modern narratives of flooding to discuss if, when, and how flood is to be considered a “natural disaster.”

Featured Image: Acqua Panna website on August 8, 2013. Retrieved via Web Archive on August 12, 2019. Copyright – 2011 Sanpellegrino S.p.A. © 2015 Nestlé

Leave a Reply