By Ann-Sophie Schoepfel

The decolonization of imperial collective imagination triggered a deep fracture in France, a fracture that has been highly visible since the 2005 suburban riots.[1] In 2020, protesters marched down the streets of Lille, Rennes, Lyon, Beauvais, Bordeaux, Le Mans, Poitiers, Marseille, and Paris to express solidarity with BLM, denouncing the grievance voiced by Black and Arab communities across France. In Paris, they covered with graffiti the statue in front of the French parliament building honoring Jean-Baptiste Colbert, a prominent statesman under ‘Sun King’ Louis XIV who wrote the Code noir, the laws governing slaves in France’s overseas colonies. This iconoclast attack echoed pressures to remove a painting commemorating the abolition of slavery in France in 1794 from the National Assembly; a painting that featured, according to scholar Mame-Fatou Niang and novelist Julien Suaudeau, “two huge black faces, with bulging eyes, oversized bright red lips, carnivorous teeth, in an imagery borrowing to [sic] Sambo, the Banania commercials and Tintin in the Congo.” In France, as elsewhere, defacing symbols of colonialism evokes complex and contradictory emotions. Officially, race does not exist as a category in the republic; many French politicians continue to hold fast to the ideal of a color-blind universalism, even if more in theory than in practice. How, then, can we understand this apparent identity crisis, which is reminiscent, for example, of the denial of racism and the imperial past in Great Britain that journalist Afua Hirsch has denounced in her recent book Brit(ish)?

Revealing the uncomfortable truth about race and identity in France today demands the expunging of modern colonial rhetoric from the articulation of contemporary European identities. This rhetoric, of course, has a long history. During the nineteenth century, the inclusion of ancient representations in modern imperial ideology bolstered colonial claims to supremacy. For Alexis de Tocqueville, ancient Greece and Rome were model conquerors to imitate and a source of justification for the Western civilizing mission: The Greeks and Romans represented “heuristic teachers,” whose lessons were inestimable for modern ideologues. Colonialism acquired a palimpsestic structure, which penetrated international governance, capitalism, and nation-state identities.

Frantz Fanon was one of the first notable theoreticians to both analyze and condemn colonialism. Based on his experience in the Algerian war of independence (1954–62), he wrote The Wretched of the Earth (1961), where he described the destructive nature of colonialism from the viewpoint of modern psychiatry. Following the path of Fanon, Edward Said, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Homi K. Bhabha, R. Siva Kumar, Dipesh Chakrabarty, Derek Gregory and Amar Acheraiou proceeded to lay the intellectual foundations of critical studies to fight against the social and political vertical hierarchies sustaining colonialism—and neocolonialism.

First coined by Jean-Paul Sartre in 1956, ‘neocolonialism’ indeed became a key concept for politicians and thinkers to depict the persisting inequalities between the global north and the global south. On the turbulent frontiers of post-imperial Asia and Africa, anti-colonial elites challenged nineteenth-century racial hierarchies by articulating alternative visions of worldmaking. Postcolonial self-determination, as Adom Getachew has persuasively argued, was not the belated fulfillment of a Euro-American legacy, an inheritance passed down from Westphalia to Woodrow Wilson. Instead, anti-colonial nationalists—such as Kwame Nkrumah and Nnamdi Azikiwe—attempted to secure a right to self-determination within the newly founded United Nations and create the New International Economic Order. Yet, their hope to create an alternate worldview of global political economy was diluted by the 1973 oil crisis and Cold War tensions. As a result, nineteenth-century economic and racial disparities persisted: Colonial practices and enduring legacies shaped existing international trade, the structure of international institutions and the global financial system. Western banking institutions profited from engagements with the slave trade, and postcolonial monetary relations between Europe and its former colonies still reinforce long-standing patterns of uneven development.

“Françafrique” is perhaps one of the most illustrative incarnations of this persistence of colonialism. In his 1999 book La Françafrique, economist François-Xavier Verschave argued that the Cold War attitudes of African leaders, such as Omar Bongo, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, or Hamani Diori, effectively created neocolonial relations between Africa and France’s former colonial peoples, featuring monopolies in situ by French multinational corporations. According to Verschave, these politicians behaved not as leaders of sovereign states but as agents of French business: Instead of fighting for decolonization, they simply accepted belonging to a community ruled by the French republic and received sizable economic assistance in return. As such, they too contributed to anchor modern colonial rhetoric in international relations.

The specter of neocolonialism also frames French and Francophone identities, as a new imperial geography has probed the evolution of collective imaginations since the former colonial possessions gained independence in the 1950s and 1960s. In his book Le syndrome de Vichy, historian Henry Rousso revealed how, from the end of World War II to the Klaus Barbie trial in 1987, France contested the memory of the Vichy experience, which was associated with the collaboration with Nazi Germany, defeat, and national humiliation. At the same time, the explosion in theoretical and historical scholarship on empires and imperialist discourses criticizing imperialism and colonialism led France to also reassess l’idée coloniale and to confront the legacies of its history as colonial power. From barriers to archival access on World War II, the First Indochina War, and the Algerian War, to controversies about the Stora report on Algeria and the rise in discourse of Islamo-leftism, we can witness a real crisis in the French collective memory—one we could, following Rousso’s work, reasonably call the imperial syndrome.

From the 1960s to the late 1980s, the French collective imagination was marked by a longing of the French imperial past. The French answer to the refugee crisis of the Vietnamese ‘boat people’, for example, heavily drew on the country’s historical ‘civilizing’ role to protect non-Western nations. In November 1978, when France decided to welcome refugees who fled Vietnam by boat and ship after the Vietnamese victory against the U.S. in 1975, deputy Joel Le Tac spoke of how France, “by tradition, has throughout time always been willing to carry the misery of those who believe in [France].” His speech was met with thunderous applause at the National Assembly: In this version, welcoming refugees from communist Vietnam represented a straight continuity with familiar imperial narratives.

Colonial nostalgia has also influenced film production. Censors banned films criticizing the French imperial past, such as Jacques Panijel’s Octobre à Paris (1962), Pierre Schoendoerffer’s La 317e section (1965), René Vautier’s Avoir 20 ans dans les Aurès (1971) or Jerome Kanapa’s La république est morte à Diên Biên Phu. Meanwhile, the longing for a colonial homeland defined the memorial tenor of popular films such as Claire Denis’ Chocolat (1988), Brigitte Rouan’s Outremer (1990), and Regis Wargnier’s Indochine (1991). In the latter’s historical epic, France’s relationship with Indochina was even presented to the viewers as a love affair, following the amorous adventure of the colonialist heroine Eliane, played by Catherine Deneuve, while her adopted daughter was ‘defeminized’ as she joined the Vietnamese national movement.

Yet, in the 1990s, when introspection concerning France’s role during the Nazi occupation was turning into a defining feature of French public discourse, the emergence of postcolonial studies and Michel Foucault’s legacy on marginalities began to slowly erode this colonial nostalgia. With the publication of his book Gangrene and Oblivion: Memory of the Algerian War, French historian Benjamin Stora broke the silence about French crimes committed during the Algerian War of Independence. The conflict soon became the focus of activists and historians who saw themselves as breaking discursive taboos that had been set up by the state.

The colonial past, too, is a “past that doesn’t pass.” Three different periods, from mourning (1954-1964) and repression (1964-1989) to the return of the repressed (1990-2005), opened up a new era characterized by a difficult anamnesis (2005-present). Beginning in 1964, repression was initiated through a series of amnesty laws for crimes committed in Algeria and was characterized by nostalgia. At the beginning of the 1990s, the work of historians as Benjamin Stora began to shatter the French silence on colonial crimes, initiating a third stage of the return of the repressed. After 2005, a real crisis of identity occurred in France, which was evidenced by a full-blown national debate on the country’s colonial past that divided not only French politicians and scholars, but most importantly society itself.

The riots in the banlieues, the emergence of the Indigènes de la République, an antiracist and anticolonial political party, and the 23 February 2005 French law on colonialism, which demanded that high-school teachers convey the positive values of colonialism, created a national uproar about the French colonial past. Associations, politicians, academics, and the media formulated a different kind of remembrance, borrowing the “devoir de mémoire,” a template of memorial activism from the success of Jewish activists, to demand memorial justice. Even high politics in France adopted memory wars vocabulary, with the conservative parties accusing those who denounced French colonial past as “islamo-leftists.” And by 2020, French statues had become a site of contestation as well.

After the 2017 series of protests in Charlottesville against the removal of Robert Lee’s statue, French memory activists Didier Epsztajn and Patrick Silberstein decided to explore the toponomy of Parisian streets and squares and published the booklet “Guide du Paris Colonial et des Banlieues,” which shows that more than 200 street names in Paris still honored the memory of French colonial statesmen, generals, and industrialists. As Epsztajn and Silberstein argue, the Parisian toponomy reveals that the French Revolution still acts as the founding myth of modern France, and that it is closely associated with historical colonial figures such as Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis-Philippe, Napoleon III or Jules Ferry. Following Gary Wilder’s argument about the close ties between colonialism and republicanism, they thus connect the prevalence of colonialism in France with the celebration of nineteenth-century industrialists and capitalists in the urban collective imaginary.

As has become clear by 2021, this imperial syndrome is not an exclusively French phenomenon. Across the sites of the former European empires, one can observe demands for the removal of symbols of colonialism from public spaces, demonstrating that the meaning carried by those statues does not represent the various communities living in the country, the city or the neighborhood in the 21st century. Cities in Belgium removed statues of King Leopold II, who personified the country’s violent colonial history with the death of more than ten million Africans in Congo between 1885 and 1908. In Berlin, local authorities of the African quarter changed colonial-era street names. In Bristol, protesters tore down the statue of slave trader Edward Colston.

Echoing the purge of Nazi symbols in European public spaces after the end of the Third Reich or the toppling of Lenin statues after the end of Communist regimes in Eastern Europe, this activist movement explicitly attacks the symbols of the Western colonial past. Demonstrators are calling for the removal of signs of racial oppression to deconstruct racism. For them, colonial, racist or slavery-era symbols are a visible barrier to decolonization and reconciliation as they embed ideas of white supremacy in public spaces. As the wounds of the French colonial past remain transgenerational and a marker of social divisions, the question of whether colonial statues must fall, or street names change, are key for the decolonization of the former metropoles from within.

[1] The author would like to express her gratitude to the Intellectual and Imperial History Working Groups of the European University Institute, Dr Milinda Banerjee, and Dr Andrew Levidis for their constructive comments on this essay.

Ann-Sophie Schoepfel is a historian of international law, professor in history at Sciences Po Paris, director of the seminar in global history and international law, and currently a Visiting Fellow at Harvard. She completed two PhDs at the University of Heidelberg and Lorraine University. Her first PhD, based on inedite sources, examined for the first time the Saigon war crimes trials in Indochina; the second reexamined the Tokyo Trial through the lens of colonialism, and re-creation of the liberal world order. Her research focuses on the history of international law, humanitarianism, migration, and memory. It was awarded the Jean-Baptiste Duroselle Prize in history of international relations. Her work has been published in peer-reviewed journals and edited volumes. At Harvard, she is completing her new monograph on the imperial origins of international law in the French empire and Global South.

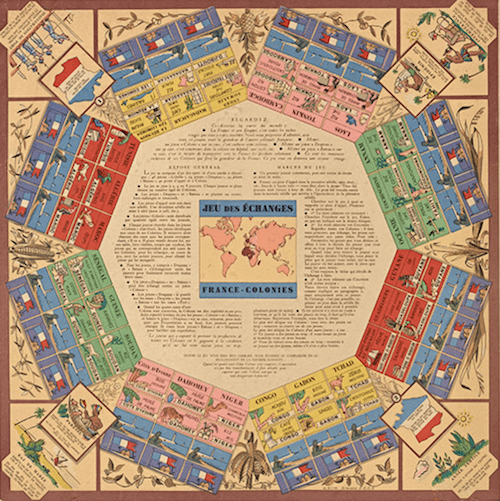

Featured Image: Trading Game: France—Colonies, 1941, O.P.I.M. (Office de publicite et d’impression), Breveté S.G.D.G. Lithograph on linen, 22 7/8 x 32 1/4 in. The Getty Research Institute, 970031.6

1 Pingback