By Beth Kearney

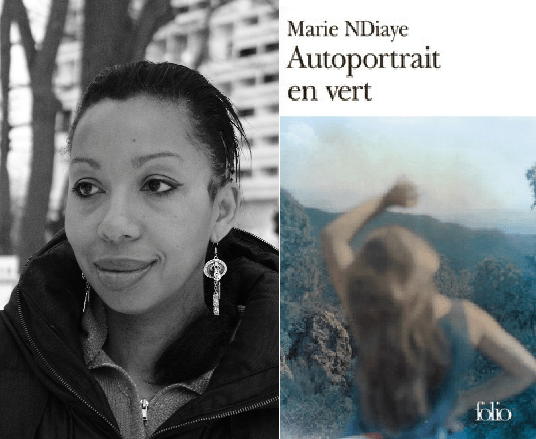

The contemporary period is marked by a noticeable change in the ways that women in the French-speaking world use text and images to represent their own lives, experiences, and identities. This shift is noticeable in twenty-first century writing by women authors of French expression, who are increasingly integrating photographs into their first-person texts. Works of this nature include, to name a few examples: Nathalie Léger’sExposition, a text staging a woman who understands aspects of her Self and personal life by contemplating photographs of another person (the captivating and enigmatic nineteenth century self-portraitist, the Countess of Castiglione); Monica Sabolo’s All This Has Nothing To Do With Me, a book using text and photographs to humorously recount a female narrator’s experience of heartbreak; and Marie NDiaye’s Self Portrait in Green, a dreamlike tale, interspersed with photographs, about a woman who indirectly contemplates aspects of herself, her family, and her origins through a series of encounters with ghostly women.

In light of this trend in contemporary women’s writing in French, often referred to as “photobiography”, a question emerges: what role does photography play in the context of self-narrative? What do the authors hope to achieve by including photographs alongside writing about their lives? One would be forgiven for thinking that when writers include photographs in their works about the Self, they would aim to introduce a degree of objectivity, and to give their reader the impression that the book conveys nothing other than truths and reality. What is a photograph if not a permanent, fixed, and objective portrayal of a real-life scene or person? Some understand photography as a medium that “fixes” the scene or person depicted, such that the photographic image is associated with notions of truth, authenticity, and evidence. Susan Sontag, for example, likens the photograph to a mirror of reality. From this perspective, a photograph is an image that anchors the individual represented in a permanent form, because their image is either printed from an analogue camera to be preserved, or permanently saved to a digital device or to “the cloud”.

In this essay, however, I argue that photographs very often introduce a degree of uncertainty to the task of self-representation, particularly when included alongside self-writing. In most works of photobiography, the “Self” is in fact portrayed as an elusive and unknowable entity ― as an identity that escapes objectivity and fixity. This in part stems from the fact that photography can often be a means of molding one’s identity and freeing it from the confines of prescribed identity roles, particularly as relates to gender and race. Photographs are, for example, quite often the outcome of staged scenarios or, particularly in this digital age, edited images. In a different sense, photographs introduce uncertainty when understood as snippets of shifting time that foreground the ephemeral nature of the present moment, as Hervé Guibert writes in his famous meditation on the “ghostly” nature of the image. They may also be considered as objects that wound the viewer, or objects onto which the viewer projects their personal memories, two ideas discussed in Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida. Similarly, a viewer may project their memories or even desires onto the photographic image because they are mourning the death of a loved one, as we see in the example of late nineteenth-century spirit photography. In short, although photographs are technically snapshots of the real world, their meaning often changes depending on the viewer and is therefore often plural.

Carrying a key tension between notions of truth and fiction ― between the real and the fabricated or imagined ― photographs play a particularly interesting role when included alongside the written word, as the text often opens up their multiple and subjective meanings. When incorporated into contemporary women’s life writing in French, photographs often amplify and reinforce textual themes of uncertainty, particularly around questions of identity.

In this way, the textual component of photobiographical works is equally perplexing. This is because women’s writing in French, particularly since the 1990s, has tended to be dominated by the genre of autofiction. These works stage a quasi-real, quasi-fictional protagonist or first-person narrator. This autofictional identity often represents aspects of the author’s own identity and allows her to explore the subjective truths of her experience but, crucially, elements of this figure are fictionalized. Identity is thus represented as a supremely uncertain category for the reader. Though the term “autofiction” was coined in 1971 by French author Serge Doubrovksy, and has proliferated in the decades following, many authors throughout all periods are ― retrospectively ― recognized as authors of autofiction: notable names in the French tradition include, for example, Michel Leiris or Marcel Proust. Readers of literature originating in English-speaking contexts would, however, be less familiar with the notion of autofiction, and more accustomed to the genres of “autobiography” or “memoir” in their strictly conventional senses. Despite this, “autofiction” is steadily being recognized as a relatively widespread phenomenon in Anglophone contemporary writing and literary history. While Sheila Heti and Rachel Cusk among the most well-known examples in English, renowned French authors such as Annie Ernaux, Marie Darrieusecq, or even the avant-garde writer Colette, are increasingly being discussed in the Anglophone world.

This blossoming of autofiction among women writing in French perhaps emerges from the fact that this genre offers a certain freedom to reinvent identity, such that women may escape from prescribed (and often gendered or racial) roles. In this way, autofiction carries a similar tension to what we see with photography: while both are often thought about in terms of “truth” and “fact,” they remain highly fictional and interpretable modes of representing identity and experience. Photobiographical works, which are often experimental and hybrid in nature, are thus most often stories around and about the Self that straddle a threshold between fact and fiction. This kind of self-representation allows women to be the creators of their own image and identity and, by blurring the boundaries between truth and fiction, they create uncertainty and portray the Self as an elusive and “unknowable” entity.

Photographs are particularly effective in upsetting this notion of a certain, knowable, and fixed Self. This is in part because photographs evoke objectivity through their association with direct and authentic representations of reality; but this is no more than an impression of objectivity, which is often subverted. Furthermore, photographs are above all images that direct a person’s gaze. This is significant, because the act of looking itself is associated with both power and pleasure, as a voyeur may experience enjoyment by looking at the fixed and immoveable image of another person. While “the gaze” refers to a kind of looking facilitated by a work of visual representation (painting, photography, sculpture, film, etc.), the male gaze has come to mean a kind of looking that frames “woman” as an individual fulfilling her socially prescribed sexual, domestic, or maternal destiny. While the concept was originally coined by Laura Mulvey in her canonical essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), it was John Berger who famously explains that the male gaze is so insidious as to damage women’s relationship with themselves. In Ways of Seeing (1972), he writes that the “surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus, she turns herself into an object ― and most particularly an object of vision: a sight” (47).

Marie NDiaye’s Self Portrait in Green is an iconic example of how photography amplifies a sense of equivocality in self-representation, essentially because it posits that a person’s visual appearance ― what one looks at ― has no bearing on a person’s authentic identity, which is in itself elusive and unknowable. To put it quite simply, NDiaye’s work seems to suggest that seeing is not believing or, more particularly, seeing does not mean knowing.

NDiaye’s supposed “self portrait” presents the curious experience of a female narrator who constantly encounters women (friends, strangers, alienated relatives) who ― for an unexplained reason ― all wear green. The narrator is haunted by these figures whom she describes as familiar to her, but who are also strange and ghostly because they are difficult to recognize and sometimes unresponsive to her. In a highly symbolic sense, these women-in-green operate as reflections of the narrator’s own Self. These encounters with spectral women symbolize the author’s own uncertain feelings toward her family and, by extension, toward the origins of her own identity. She experiences a sense of alienation, mixed with disquieting familiarity, toward the people that she identifies as women-in-green: maternal figures (mother and stepmother), estranged siblings and friends, and the paternal homeland (Africa). The text therefore evokes the narrator’s mistrust of a series of women that she meets in her hometown in regional France and on her travels, encounters that symbolize the uncertainty she experiences in grappling with aspects of her own identity. Crucially, the author does not bring any certainty to the readerly experience: the women-in-green, as well as the narrator’s feelings toward her family, origins, and identity, remain an ambivalent aspect of the book. Meaning is only found in the fact that they point to the elusive and uncertain nature of outward appearances and of identity itself.

The photographs scattered throughout NDiaye’s book do not introduce objectivity or certainty; on the contrary, the images amplify this notion of the unknowability and uncertainty of identity. This is in part because they recreate, for the reader, the narrator’s experience of confusion when faced with figures that she can see, but that she struggles to know andto understand. Produced by the visual artist Julie Ganzin, the photographs are a series of blurred portraits of a woman who, with blonde hair and pale skin, turns her face away from the camera. These images of an unknown, blurred female figure in a blue-green environment evoke the women-in-green described in the text. Importantly, these images do nothing to clarify the narrator’s strange experience of ghostly women-in-green; the women in the photographic portraits echo textual themes of strangeness, spectrality, and equivocality. Not only do the women represented turn their face and body away from the camera, the images themselves are also blurred to obscure the contours of the people and environment.

NDiaye’s women-in-green, and their reappearance throughout the book in both its text and images, operate as a metaphor for the author’s relationship to the aspects of her own identity that she refuses to pin-down ― aspects that she chooses not to convey or express in an objective sense. Specifically, we may interpret the women-in-green as characters that point to the author’s African heritage, a heritage that she cannot embrace (she was born and raised in France) and that is manifest only through her skin color and last name (NDiaye looks like an African woman and carries an African last name, but she does not identify culturally with this aspect of her heritage). In the public sphere, NDiaye expresses that she does not identify with her Senegalese culture. It is thus important to note that, in Self Portrait in Green, NDiaye chooses to include images of a pale-skinned blonde woman, a figure that does not at all resemble the author herself. Though the work is titled a “self portrait”, these images clearly do not depict NDiaye, and the women-in-green of the text are only ghostly figures that represent fragments of the author’s Self ― specifically, they represent the author’s refusal to assume, and fully identify with, the African identity thrust upon her. This way of portraying aspects of the Self ― whereby identity is, as Andrew Asibong writes, “blanked” ― foregrounds the arbitrary nature of visual signs of a specific identity: NDiaye’s skin color is no more indicative of her “true” identity than the color green; visual traces of NDiaye’s Senegalese heritage have no bearing on her “authentic” culture or identity. The photographs of Self Portrait in Green thus represent elusive and largely unrecognizable figures to show that what is seen is not always the truth, an idea that undermines the notion that identity itself can be known in concrete and objective terms.

This “blurring” of the Self is implicitly political and bears ramifications for how we think about identity in France today. Shirley Jordan, a scholar of women’s writing in French, explains that NDiaye’s fictional universe at large interrogates the notion of inhospitality, in part through the idea that many experience discomfort when faced with paradox in identity categories. Crucially, Jordan explains that inhospitality may be considered postcolonial in nature: France may be judged incapable of welcoming complex identity categories, an attitude illustrating the nation’s inability to come to terms with its troubling colonial legacy. In this way, NDiaye’s refusal to identify with the African identity that is prescribed to her emerges in force in Self Portrait in Green: the women-in-green symbolize the narrator’s mistrust of her origins and her refusal of the label “African woman”. The photographic portraits amplify this message. The hazy blue-green aesthetic of the photographs is thus a visual feature that actively inhibits an objective view of the women represented. In this way, like many authors participating in the contemporary photobiography phenomenon, NDiaye defiantly portrays a “blurred” and, ultimately, unknowable Self.

Beth Kearney is a PhD candidate at the University of Queensland (Australia) in French Studies. Her scholarly interests are broadly anchored in the fields of modern and contemporary literatures, cultures, and visual studies in French. She is specifically interested in women’s writing in French, and the ways that the formal properties of their work influence their (often political) content. As the above text illustrates, her current PhD project focuses on the interactions between photography and the written word in contemporary women’s photobiography in French.

Featured Image: Marie Ndiaye, 2013, and the cover of her Autoportrait en vert (2006), courtesy of Gallimard.