By guest contributor Joel S. Davidi

In my last post on the history of the first of Nisan as a Jewish new year I discussed the history of this now mostly forgotten holiday into the tenth century. Until this point, this festival was celebrated among the Jews of Eretz Israel as well as their satellite communities across the Middle East (including a small “Palestinian-rite” contingent in Iraq itself). Over the next one hundred years, however, the celebration of the first of Nisan became the domain of only a very small minority of Jews. In a large measure, this was due to the long standing disagreements between the two great centers of Jewish learning at the time, Eretz Israel and Babylonia/ Iraq.

All in all, the competition between Babylonia and Eretz Israel ended in a decisive Babylonian victory. This was due to several factors not least of which is the fact that Babylonian Jewry experienced much more stability under Sassanian and later Islamic rule while its Eretz Israel counterpart was constantly experiencing persecution and uprooting. The final death knell for Minhag Eretz Yisrael was delivered in July of 1099 when an army of Crusaders broke through the walls of Jerusalem and massacred the city’s Jewish inhabitants, its Babylonian-rite, Palestinian-rite communities and Karaite communities. With the destruction of its center began the decline and eventual disappearance of many unique Eretz Israel customs. It is only due to the discovery of the Cairo Genizah that scholars have become aware of many of those long-lost traditions and customs. At this time Babylonia’s prominence began to decline as the Sephardic communities of the Iberian Peninsula and the Ashkenazic communities of France and Germany were increasingly on the ascendancy. Both of these communities, however, maintained the Babylonian rite. (As Israel Ta Shma points out in his book on early Ashkenazic prayer, both the Sephardic and Ashkenazic rites have Eretz Israel elements. These are more evident in the Ashkenazi rite, probably due to the ties between the proto Ashkenazim and the Palestinian academy Academy in Byzantine Palestine.)

The latest evidence the celebration of the first of Nisan comes to us from the 13th century and it would seem that even by this time it was all but stamped out by those who were determined to establish the primacy of the Babylonian school. This period coincides with the increased activism of Rabbi Abraham Maimonides, the son of Moses Maimonides, the great Spanish codifier of Jewish law. Rabbi Abraham, who championed standardization based on his father’s codification, exerted great pressure against the Synagogue of the Palestinians in Fustat, Old Cairo to bring their ritual into line with Babylonian standards. He was for the most part successful but, as we have already seen, this unique custom was retained (albeit in diminished form) among Egyptian Jews to this very day.

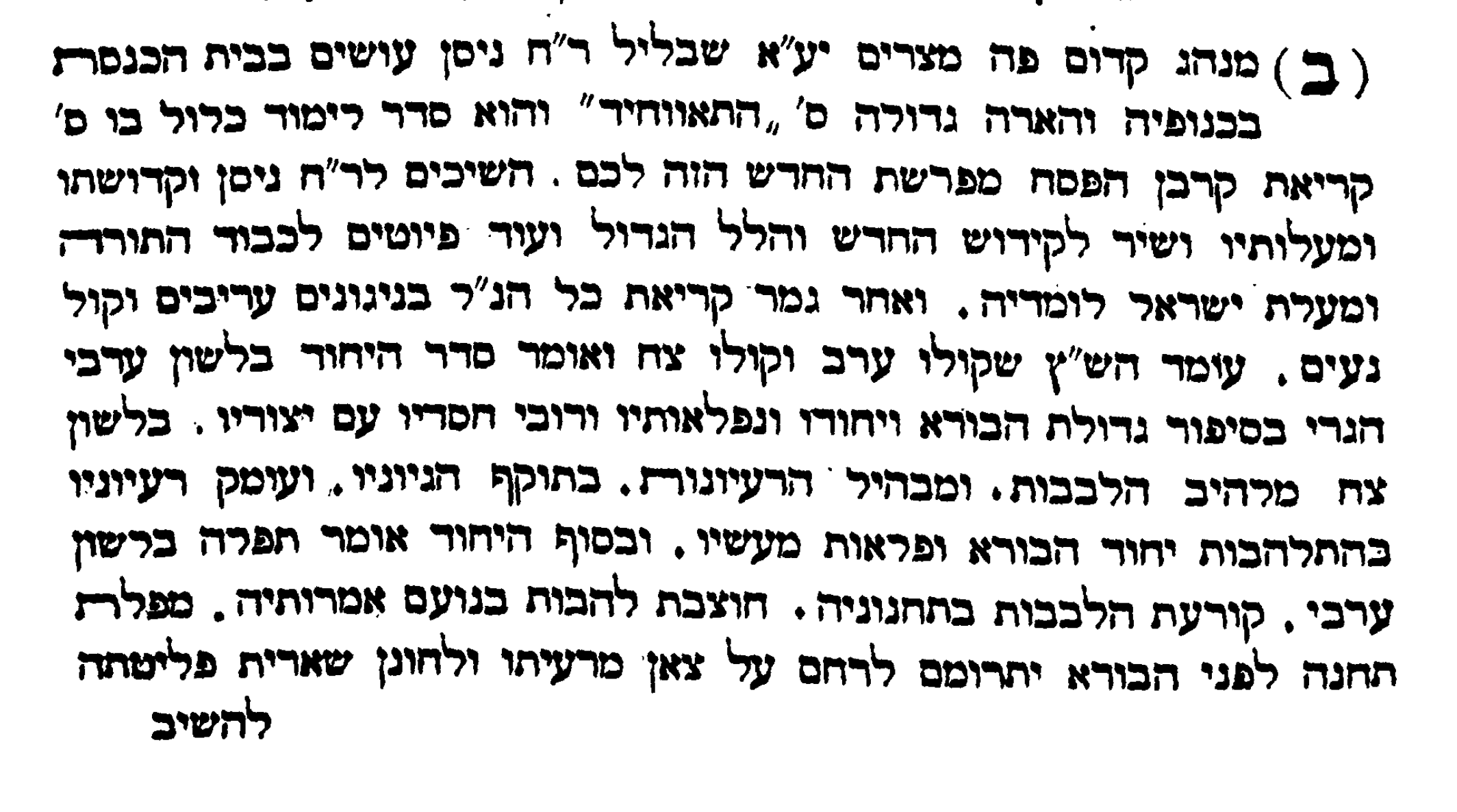

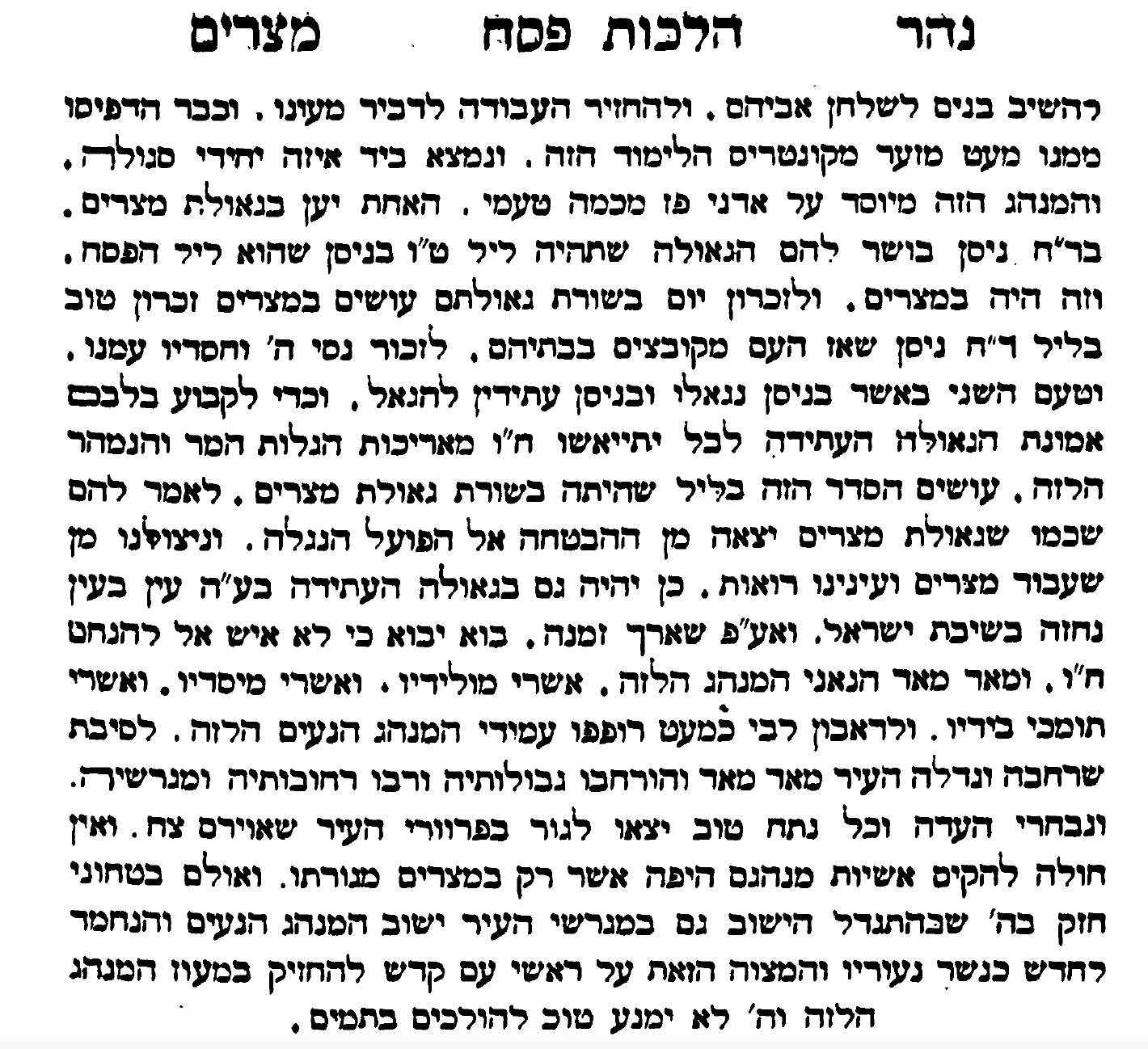

In an April 20, 1906 article for the English Jewish Chronicle, Herbert Loewe provides an eyewitness account of an Al-Tawhid ceremony in the fashionable Abbasiya neighborhood of Cairo. Two years later, a more detailed description was recorded by the Chief Rabbi of Egypt, Refael Aharon ben Shimon in his book Nehar Misrayim (p. 65-6).

I reproduce it here (courtesy of Hebrewbooks.org):

After extolling this “beautiful custom”, ben Shimon laments how the custom had become so weakened and how so many had become lax in keeping it. He states that this was largely due to the fact that the city had experienced such large scale expansion and many members of the Jewish community had relocated to the suburbs. He concludes on an optimistic note with the hope that the custom will experience a renaissance in the near future.

Two other North African Jewish communities that I know of retain more pared-down versions of the celebration of the first of Nisan. In the communities of Tunisia and Libya, the ceremony is referred to as bsisa (and also maluhia). Bsisa is also the name given to a special dish that is prepared for this day which is made of wheat and barley flour mixed with olive oil, fruits and spices. Several prayers for the new year are recited whereupon the celebrants exchange new year greetings with each other. Many of these prayers contain similar themes to the Egyptian-Jewish Tahwid prayers I discussed in part I of this article. (For example: “Shower down upon us from your bounty and we shall give it over to others. That we shall never experience want– and may this year be better than the previous year.”) As in the Egyptian community, however, the new year aspect of the celebration is not especially stressed. As the eminent historian and expert on North African Jewry Nahum Slouschz points out in an article in Davar (April 7, 1944), “It is impossible not to see in these customs the footprints of an ancient rosh hashanah which was abandoned with the passage of time because of the tediousness of the Passover holiday and in favor of the holiness of the traditional [Tishrei] Rosh Hashana.”

(For more on the roots and contemporary practice of bsisa and maluhia see here, here, here, and here. For videos of the bsisa/ maluhia ceremony see here, here, and here.)

Although the observance of the First of Nissan is no longer as prominent as it once was in rabbinic Judaism, the two most prominent non-rabbinic Jewish communities, the Karaites and the Samaritans, have maintained the holiday into recent times. The Cairo Genizah contains leaves from a Karaite prayer book containing a service for the first of Nisan. This custom eventually fell out of the Karaite textual record as Karaite traditions fell in line with Rabbanite ones over the later middle ages. In his monumental study of the now extinct European Karaite community, historian Mikhail Kizilov discusses how Eastern-European Karaites underwent a gradual process of “dejudaidization” and “turkification” in the 1910s-20s. This was largely due to the work of their spiritual and political head, Seraya Shapshal, who, aware of growing Anti-Semitism in Europe, was determined to present his flock as genetically unrelated to the Jews (claiming instead that they were descendants of Turkic and Mongol tribes). He likewise sought to recast Karaism as a syncretistic Jewish-Christian-Muslim-pagan creed. Among the reforms instituted by Shapshal was the changing of the Karaite calendar. Although the Karaites of old began the calendar year on Nisan, as per Exodus, they had long assimilated the Rabbinic custom of beginning the year in Tishrei. Shapshal sought to avoid a lining up of the Karaite and Rabbanite new years which is why he switched the Karaite new year to March-April, thereby ironically reverting back to the ancient Karaite custom. This particular reform never took off and the community continued to celebrate the new in year in Tishrei. Even the official Karaite calendars printed that date (which like the Rabbanites they called “Rosh Hashana”). Currently, Karaites do not actually celebrate this day or recite any special liturgy, however they do nominally recognize this day as Rosh Hashanah and they will exchange new year tidings.

Samaritans preserve the most extensive observance of this day. According to the Samaritan elder and scholar Benyamim Sedaka, the Samaritans celebrate the evening of the first day of the first Month – The Month of Aviv – as the actual Hebrew New Year. They engage in extended prayers on the day followed by festive family gatherings. They likewise bless one another with the traditional new year greeting “Shana Tova” and begin the observance, as the followers of the Palestinian rite once did, on the Sabbath preceding the day. The entire liturgy for the holiday is found in A. E. Cowley’s “The Samaritan Liturgy.” The fact that the Samaritans, who have functioned as a distinct religious community from Jews since at least the second century BCE, observe this tradition is the greatest indicator of its antiquity. The antiquity of this custom is also suggested by the fact that the springtime new year is likewise celebrated by many other ethnic communities from the Middle East including the Persians and Kurds (who call it Nowruz) and also, much closer to Jews linguistically and culturally, the Arameans and Chaldeans/Assyrians who call their New Year Kha (Or Khada) B’nissan (the first of Nissan) .

Siddur Eretz Yisrael, published by Machon Shiloh

Minhag Eretz Israel is now effectively extinct. Today, however, there is a small community of predominantly Ashkenazic Jews in Israel who seek to reconstruct this rite. Using the work of scholars who have labored to piece the Palestinian rite together based on the Cairo Genizah, this community endeavors to put it back into practical usage. Among many other customs, they celebrate the First of Nisan. The flagship institution of this movement is called Machon Shiloh and its founder and leader is an Australian-Israeli Rabbi named David bar Hayyim. In correspondence with me, Yoel Keren, a member of Machon Shilo, stated that his community observes the festival in the manner prescribed by the Geniza fragments. On the eve of the first of Nissan, the community waits outside to sight the new moon, then recites the kiddush prayer and finally sits down to a festive meal. The community has also recently published a prayer book called Siddur Eretz Yisrael, which is based on the ancient rite. You can listen to some prayers recited in this rite here, here, and here.

For an interesting interview with Rabbi Bar-Hayyim about the rite and its contemporary usage see here.

Appendix to Part I

Since publishing my original post about the first of Nissan’s history as a Jewish holiday a few other sources have come to light about the history of the day’s significance. Here are a few of the earliest sources that mention the day as a holiday (my thanks to Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein for bringing some of these to my attention).

The earliest of these comes from the book of Ezekiel (45:18-19):

Thus saith the Lord GOD: In the first month, in the first day of the month, thou shalt take a young bullock without blemish; and thou shalt purify the sanctuary.

Ezekiel contains numerous laws and festivals that are not found in the Pentateuch. Many interpret these as being meant for a future (third) Temple. Ezekiel does not explicitly describe the first of Nissan as a celebration of the new year per se but this description is nonetheless the earliest evidence of the day having special significance.

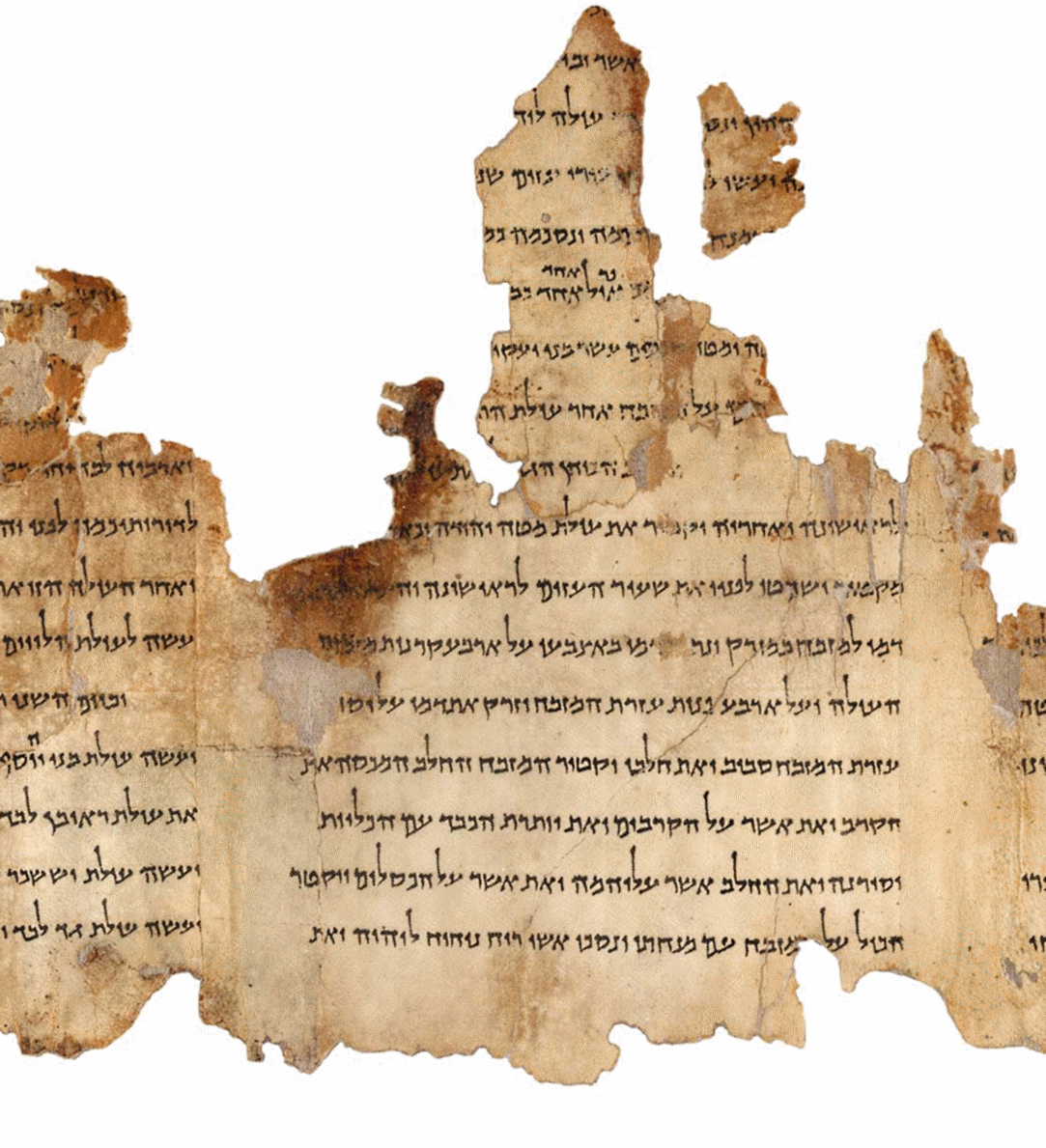

We find a similar reference in the Temple Scroll (11Q19) of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Temple Scroll describes the ideal Temple of the Qumran sectarians. The Festival of the first day of the first month (Nissan) is one of three additional extra-biblical festivals that are mentioned in this work:

On the first day of the [first] month [the months (of the

year) shall start; it shall be the first month] of the year [for you. You shall

do no] work. [You shall offer a he-goat for a sin-offering.] It shall be

offered by itself to expiate [for you. You shall offer a holocaust: a

bullock], a ram, [seven yearli]ng ram lambs [without blemish] …

[ad]di[tional to the bu]r[nt-offering for the new moon, and a grain-

offering of three tenths of fine flour mixed with oil], half a hin [for each

bullock, and wi]ne for a drink-offering, [half a hin, a soothing odour to

YHWH, and two] tenths of fine flour mixed [with oil, one third of a hin.

You shall offer wine for a drink-offering,] one th[ird] of a hin for the ram,

[an offering by fire, of soothing odour to YHWH; and one tenth of fine

flour], a grain-offerin[g mixed with a quarter of a hinol oil. You shall

offer wine for a drink-offering, a quarter of a hin] for each [ram] …

lambs and for the he-g[oat] .

Joel S. Davidi is an independent ethnographer and historian. His research focuses on Eastern and Sephardic Jewry and the Karaite communities of Crimea, Egypt, California and Israel. He is the author of the forthcoming book Exiles of Sepharad That Are In Ashkenaz, which explores the Iberian Diaspora in Eastern Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. He blogs on Jewish history at toldotyisrael.wordpress.com.

October 4, 2017 at 4:48 pm

Reblogged this on Project ENGAGE.

October 4, 2017 at 6:00 pm

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

October 16, 2017 at 1:20 pm

Thanks for this wonderful insight into the geographic and sectarian currents that may have affected the current normative Jewish Calendar. I wonder if there is any evidence of the impact of Christianity’s hijacking Nissan/Passover as the seminal period of re-birth and redemption that might have caused Rabbinic Judaism to eject the Nisan New Year and empower the Tishrei alternative narrative. I have argued in a blog post (https://madlik.com/2014/04/06/the-gospel-geniza-part-2/ ) that “as a result of Christianity monopolizing the Passover deliverance narrative, Judaism dialed down both the preparations and build-up to Passover as well as the inherent messianic overtones of the holiday.” Similarly, the 40 day preparation period (that would parallel the Elul preparation to RH and YK) was also de-emphasized culminating in a total eclipse of Shabbat Hagadol which is referenced in John 19:31 but in Jewish sources, does not appear (or re-appear) until the 12th century in the Mhzor Vitry (see https://madlik.com/2014/04/11/the-gospel-geniza-part-3/ ) …